Incorporating Maker-Centered Learning into the Early Years Classroom

Victoria Educational Organisation educator and Head of Curriculum Studies Lisa Golds provides an introduction to the Agency by Design: Early Childhood in the Making initiative and offers a first glimpse into the emergent themes and new puzzles surfacing from the project.

In February 2018, the Victoria Educational Organisation (VEO)—a network of trilingual nursery schools and kindergartens across Hong Kong—joined Project Zero to embark on an exploratory research initiative geared towards supporting 3–6 year-old students, as they encountered maker-centered learning for the first time. Aptly named, the title of this initiative is Agency by Design: Early Childhood in the Making.

Funded by the CTF Education Group, the Agency by Design: Early Childhood in the Making research initiative aims to understand how the practices and pedagogies of maker-centered learning can be adapted — or hacked — to support our youngest learners as they take their first steps into the world of education.

Initially, our discussions around maker-centered learning in the early years generated a number of puzzles including;

- How can we ensure that the language of maker-centered learning is age-appropriate, and understood by young learners?

- Is it safe for such young children to use analogue tools for taking objects apart—and making?

- Can children as young as 3 years-old truly show empathy towards others?

- How much scaffolding or front-loading would be necessary to develop students’ skills and conceptual understanding in regards to making and design?

Considering the puzzles above, 12 of our teachers, across two campuses in Hong Kong, skilled-up on making by taking the Thinking and Learning in the Maker-Centered Classroom online course and then wrote and defined individual research questions that they began to pursue. Bi-weekly meetings on campus, and support from the team at Project zero — including Edward Clapp, Carolyn Ho, Katy Laguzza, Andrea Sachdeva, and Lynneth Solis —have given the VEO teachers ample opportunity to discuss their findings, analyse their students’ work and their own practice, and plan next steps for incorporating maker-centered teaching and learning into their classrooms.

As we look back at our experiences incorporating maker-centered learning into our early years settings, a number of interesting themes, highlights —and new puzzles— have begun to emerge.

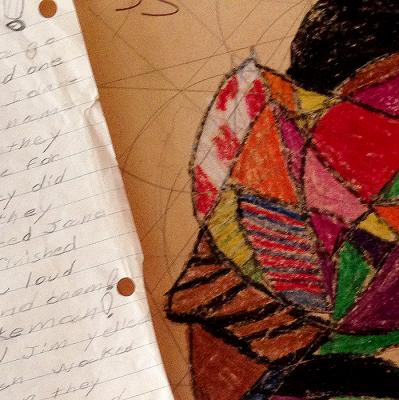

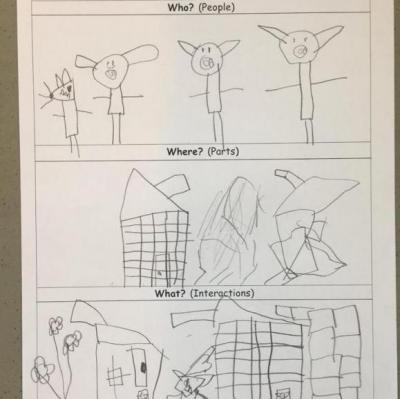

One concern voiced by many of the teachers was that the language embedded within the Agency by Design framework for maker-centered learning was too difficult for young learners to comprehend. Concepts such as complexities, perspective taking, and values can be hard for young people to grasp and the teachers questioned whether the Agency by Design thinking routines and other tools and resources using such language would be meaningful for our students. In reality, the teachers and students were able to approach the Agency by Design tools and resources, especially the thinking routines, in a way that allowed for tinkering and hacking that seemed to come naturally to early years teachers. For example, when comparing two stories about The Three Little Pigs, one teacher asked the children to consider Where it was (Parts), Who was there (People), and What happened (Interactions), as opposed to using the original Agency by Design language, Parts, People, Interactions. Using such scaffolding, the teachers and students were able to work together to co-construct what these terms meant to them.

We were also very excited to be introduced to the making moves, which break down the three maker capacities into smaller focused actions—and provided us with indicators of the maker capacities as we observed children in our classrooms. We recognised how much these making moves came into play with our youngest students, offering concrete examples of how to take part in maker-centered learning throughout a range of simple activities.

Safety is an obvious concern when working with small children, but the teachers succeeded in providing the children with a number of opportunities to build upon their tool handling skills. Take apart activities were facilitated in a number of ways, including teacher demonstrations acting as frontloading experiences for the students, followed by small group work, allowing the teachers to devote attention to each child’s safety. Exposing our students to new analogue tools was always greeted with excitement and a degree of respect—the children were fully aware that these tools could be dangerous if they weren’t handled safely. Tools such as screwdrivers were handled with care, tiny screws were carefully placed aside for later. Fine motor skills were developed from these experiences—not to mention the capacities for looking closely and exploring complexity!

New technology was introduced to the children as well. Our 3 year-olds were excited to be trusted with their own digital cameras to document what they had observed around their school, and with a little bit of practice they were able to produce photographs that evidenced their learning.

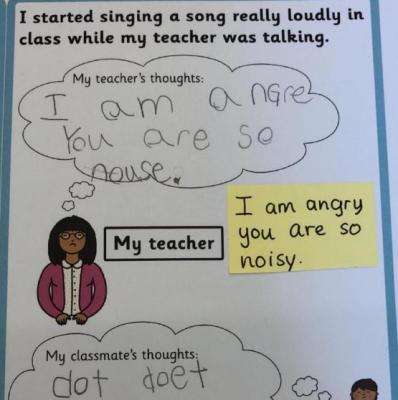

It was noted by the teachers participating as part of the project that many children aged 3–5 years-old have trouble understanding the emotions of others when considering an abstract situation. A lot of scaffolding has therefore been given to the children to support them in building skills in perspective-taking and empathy. The teachers have found that through role play and high-quality picture books, our students are able to reflect upon their own lived experiences, allowing them to name feelings that may be felt by other people. At first, we found that children could only name the emotions happy and sad and so throughout the academic year, the children have been introduced to a wide variety of emotion words such as frustrated, disappointed, and joyful, which we now observe them using in their daily exchanges. This widening of the children’s vocabulary has enabled them to see shades of emotions that exist under the umbrella of happy and sad, and we believe that it has helped them to understand the variety of emotions that can be felt, both by themselves and by others.

As we move ahead with this exciting work, our teachers have discussed a number of new puzzles and questions during our biweekly meetings, including;

- How can we ensure that students are being agentic—what are some ways to make individual and collective agency visible for young learners?

- How can we prompt such young children to engage in meaningful self-reflection?

- How has making in the classroom changed our perspective towards inquiry-based learning and teaching?

- How can we communicate the benefits of maker-centered learning to other early years teaching staff within our organisation—and beyond?

We believe that addressing these questions can help us to look forward to a new stage of development as a learning community, and support educators who may likewise be asking these questions about the relationship between maker-centered learning and early years education in other settings around the world. We are excited to carry on this work and to hopefully uncover more answers—and more puzzles—along the way.